Who Can We Rely On When the Watchdogs Are Not Doing Their Jobs? Whistleblowers.

Last year we described the immense job facing the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), the U.S. agency charged with regulating financial markets.

The SEC’s staff of 4,459 people is responsible for overseeing nearly every part of the United States’ $110 trillion capital markets. That’s about $24.7 billion per person—more than the entire value of Rupert Murdoch’s media empire. Moreover, this requires oversight of more than 28,000 registered entities (including investment advisers, mutual funds, exchange-traded funds, broker-dealers, municipal advisors, and transfer agents), 7,400 reporting companies, 24 national securities exchanges, 9 credit rating agencies, and 7 active registered clearing agencies.

This burden is why the SEC relies, in part, on independent auditors and accountants as “watchdogs” to curb abuses and protect investors.

Chief among these watchdogs are the “Big Four”—accounting firms Deloitte, Ernst & Young (EY), KPMG, and PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC). In 2021, the Big Four audited more than 90 percent of the largest public companies (“large accelerated filers”).

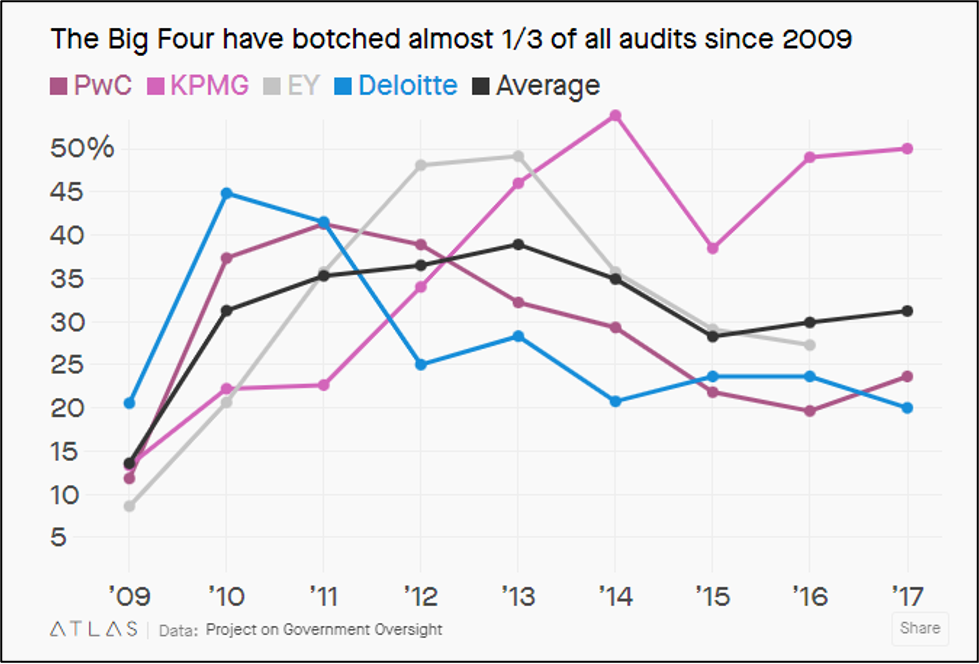

However, the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (“PCAOB” or “peek-a-boo”)1, has repeatedly found widespread and substantial deficiencies in audits conducted by the Big Four. In its inspection of a sample of 2017 and 2016 audits, PCAOB found 20% of Deloitte’s audits to be inadequate, 23.6% of PwC’s, 27.3% of EY’s, and 50% of KPMG’s. When an audit is found to be “inadequate,” it means that if the audited company had reported erroneous financial results or engaged in accounting fraud, the audit may not have detected these problems.

These deficiencies are not anomalies; they are reflective of a long pattern:

In 2022 alone, the Big Four collectively audited over 1,900 the largest public companies – making them responsible for oversight of at least $1.37 trillion worth of company equity in the hands of public investors.

Applying the deficiency scores from PCAOB’s review of 2017 and 2016 audits cited above, the Big Four inadequately audited, at minimum, investments of about $399 billion. That’s like saying they inadequately audited an amount equal to the entire GDP of Norway!

That’s the GDP of Norway! Enough to buy a house for every man, woman, and child in Delaware and still have $65 billion left over.

Conflicts may contribute to this problem. “Independent” auditors are paid by the companies they scrutinize, resulting in pressure to produce reports that please those companies. A recent academic study of 13 years’ worth of data on 358 U.S. audit firms found that, on average, auditors saw a 2.2 percent drop in their client growth for each flaw they highlighted, while their revenue grew 8 percent less than competitors who didn’t flag those flaws.

In March of this year, the SEC launched a probe into the Big Four’s conflicts of interest policies, concerned that their sale of consulting and other non-audit services might undermine their ability to conduct independent reviews of public companies’ financials. All four firms have paid fines to the SEC in the last 8 years to settle prior regulatory investigations of audit independence violations.

Other regulatory agencies have also taken note of the issues that arise where an accounting firm is responsible for auditing its own work. For instance, in 2014, the I.R.S. challenged what it called a “sham” tax arrangement devised by EY for its client Perrigo to allow the drug company to avoid more than $100 million in federal taxes. Perrigo’s then auditors, accounting firm BDO, questioned the propriety of the arrangement. Shortly thereafter, Perrigo replaced BDO with EY as its auditor. EY proceeded to bless the arrangement designed by its colleagues. The IRS has challenged similar offshore arrangements undertaken by Coca-Cola, Facebook, and Western Digital. In all of those cases, the accounting firm that constructed the elaborate tax plan later signed off of the company’s books in its capacity as an independent auditor.

We expect to see significant enforcement activity resulting from the SEC’s announced probe. Just a few months ago, the SEC imposed a $100 million fine on EY—the largest penalty ever imposed by the SEC against an audit firm—for “failure[] to act with the integrity required of a public company auditor.” (KPMG paid $50 million to settle similar charges in 2019.)

The SEC charged, and the firm admitted, that EY audit professionals cheated on exams required to obtain and maintain their licenses as Certified Public Accountants (CPAs) and that EY withheld evidence of this misconduct from the SEC during the Enforcement Division’s investigation of the matter. Specifically, EY audit professionals cheated on the ethics component of CPA exams and various continuing professional education courses required to maintain their CPA licenses, including ones designed to ensure that accountants can properly evaluate whether clients’ financial statements comply with Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP).

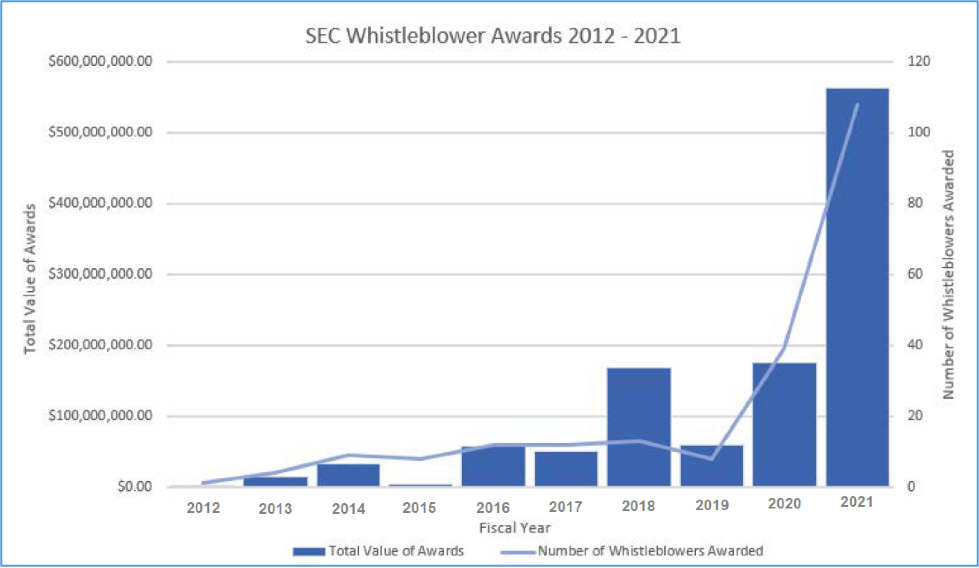

The SEC has a huge job to do. A job which is, unfortunately, not always made easier by the watchdogs who are supposed to ease the load. But there is one group who can always be relied on as a crucial law enforcement partner: whistleblowers. As SEC Chair Gary Gensler commented, “Whistleblowers provide a critical public service and duty to our nation, taking personal and professional risks in doing so. Since the [SEC whistleblower] program’s inception, enforcement matters brought using information from whistleblower have resulted in more than $1.3 billion that has been (or is scheduled to be) returned to harmed investors.”

In fiscal year 2021, the SEC announced that it had filed 434 new enforcement actions, 697 total enforcement actions, and obtained judgments and orders for nearly $2.4 billion in disgorgement and more than $1.4 billion in penalties. Among these were several actions specifically intended to “ensur[e] gatekeepers live up to their obligations.”

Notably, the SEC whistleblower program also notched a banner year, awarding a record $564 million to 108 whistleblowers (bringing the total awarded over the life of the program to over $1 billion) and awarding record-setting awards of $114 million and $110 million.

Written by Molly Knobler of Phillips & Cohen. Edited by Kate Scanlan of Keller Grover LLP and Tony Munter of Price Benowitz. Fact checked by Julia-Jeane Lighten of Taxpayers Against Fraud.

1. PCAOB is a non-profit entity under the SEC’s purview which serves as a “watchdog” of the supposed “watchdog” auditing companies.