A Brief History of False Claims Act Constitutionality

The False Claims Act (FCA) prohibits the submission of false or fraudulent claims to the United States government. The FCA includes a qui tam provision, which allows private individuals who allege that a defendant submitted false claims to file a case and pursue damages on the government’s behalf. These individuals, known as “relators,” file a complaint under seal outlining the alleged fraud, and the case remains under seal while the government investigates the allegations. The government then decides whether it will intervene in the litigation. If the government declines to intervene in the litigation, the FCA authorizes the relator to litigate the case on the government’s behalf, with the government getting the lion’s share of any recovery.

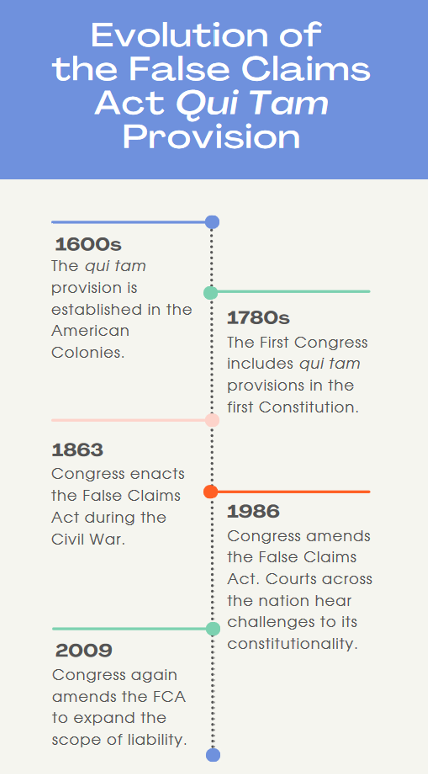

The American colonies began using qui tam statutes in the 1600s as an extension of European practice, and the First Congress included qui tam provisions in the first framing of the Constitution.[1] Congress enacted the FCA with its qui tam provision in 1863 as a means of redressing fraud perpetuated on Union troops. In 1986, Congress amended the FCA to expand liability for fraud to include all government contracts and claims, not just those submitted to the military, and, in 2009, Congress passed the Fraud Enforcement and Recovery Act (FERA), which further expanded the scope of liability for those fraudulently receiving money from the federal government.

Although qui tam statutes date back hundreds of years, defendants have challenged the constitutionality of the FCA for nearly as long. After the 1986 Congressional amendments to the statute, courts across the country heard suits contesting the constitutionality of the qui tam provision. This surprised proponents of the provision because the 1986 amendments expanded the power and control of the Executive Branch throughout the duration of a relator’s suit. Despite the numerous challenges, every appellate court to have addressed the issue has ruled in favor of the FCA qui tam provision’s constitutionality. In 2009, after Congress amended the FCA again, defendants continued to contest the constitutionality of the Act. One of the major changes in the 2009 amendments is that it expanded FCA liability to those using government funds inappropriately, even if they were not procuring goods or services directly for the government.

The challenges to qui tam constitutionality fall under two clauses of Article II, the Take Care and appointment clauses, or a clause of Article III, the standing clause. The Take Care clause defines the power and duties of the Executive Branch, and opponents to the FCA’s constitutionality argue that the qui tam provision infringes on the ability of the Executive Branch to fulfill their duty to enforce laws and seek justice for the government. Defendants argue that private citizens do not have the authority to bring cases on behalf of the United States; this is a power that is vested in the Executive Branch alone. However, these arguments ignore Executive Branch officials’ significant power over cases brought by relators and that the qui tam provision expands, rather than inhibits, the power of the Executive Branch. Many government recoveries from the FCA would not be possible without the ability of private citizens to act as whistleblowers and bring cases on behalf of the government.

The appointment clause requires the Executive Branch to appoint officials. Critics question whether relators should be able to perform a duty of the Executive Branch by bringing cases without having been appointed as government officials. However, relators do not have the same powers as officers of the United States, which eliminates the need for their appointment.

Finally, to have standing under Article III, those who bring a case must have a “personal injury in fact,” a requirement that defendants have contended relators fail to meet. However, the ruling of a 1999 case, Vermont Agency of Natural Resources v. U.S. ex rel. Stevens, settled the matter by stating that relators have standing through partial assignment by the government.

Fundamentally, the FCA’s qui tam provision is rooted in centuries of history and legislation and the recent arguments made by defendants in FCA cases do not hold water. Because of its qui tam provision, the FCA is the government’s most effective fraud fighting tool, and there is no Constitutional or historical basis for eliminating it.

Rosie Tomiak is the Public Interest Advocacy Fellow of The Anti-Fraud Coalition

[1] Vermont Agency of Natural Resources v. United States ex rel. Stevens, 529 U.S. 765 (2000)