How The SEC Regulates $29 Trillion in Equities

Willie Sutton, a notorious bank robber in the 1930’s was once asked why he robbed banks. His answer, found on the FBI’s Famous Cases page, was: “Because that’s where the money is.”

Today’s FBI identifies corporate fraud, including securities fraud, as one of its highest criminal priorities because of the potential for significant losses to investors and harm to the overall economy. According to the FBI, “[t]he creation of complex investment vehicles and the tremendous increase in the amount of money being invested have created greater opportunities for individuals and businesses to perpetrate fraudulent investment schemes.”

The amount of money in today’s financial markets is staggering. The Securities and Exchange Commission, the U.S. agency with responsibility for regulating securities markets, estimates that “American households own $29 trillion worth of equities – more than 58% of the US equity market – either directly or indirectly through mutual funds, retirement accounts and other investments.”

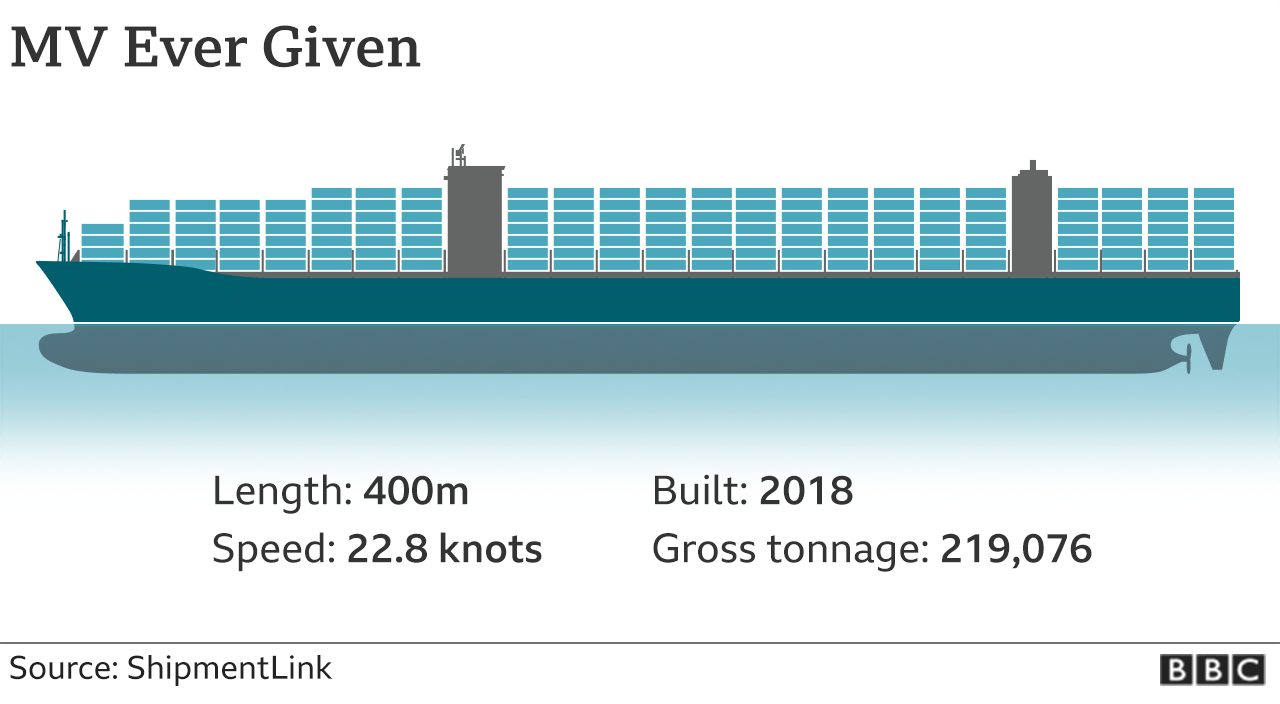

With numbers this large, it’s hard to imagine what that even looks like. Here’s one way to think about it: If the $29 trillion in equities owned by American households was $50 bills, it would fill all the cargo space in the EVER GIVEN, the massive container ship that ran aground and blocked the Suez Canal in April 2021.

Willie Sutton would have loved a “bank” the size of the EVER GIVEN with $29 Trillion in it, but today’s money is not held in one place, or even by one entity. More than 7,400 reporting companies and 28,000 registered entities in the securities industry, including investment advisers, broker-dealers, and securities exchanges, hold and transfer SEC-regulated funds through complex electronic networks involving sophisticated computerized tools that have given “unprecedented opportunities” to participate in global capital markets.

While the FBI has identified the increased opportunities for securities fraud in current systems, it is difficult to quantify how much fraud actually may exist. A study conducted in 2000 estimated as much as $40 billion in securities fraud each year.

Whether greater opportunities of fraud could lead to $40 billion or more in losses today, the number of civil servants working in the federal government to monitor the more than 7,400 reporting companies and 28,000 registered entities involved in trading $97 trillion annually is frighteningly small.

In 2020 the SEC had 4,706 employees. Of that total, only about 28% (1,352 employees) are assigned to enforcement activities. The SEC’s Office of the Whistleblower, the Office created as a part of the Dodd-Frank Whistleblower program, is staffed by just 16 attorneys.

By way of illustration, for the SEC which oversees trading of $97 trillion every year, it would be like monitoring the loading and unloading of enough $10 bills to fill fifteen ships the size of the EVER GIVEN – with several trillion left over. And for the Office of the Whistleblower, which fields tips across all the SEC’s regulated activity, it is roughly one ship for every lawyer in the SEC’s Whistleblower Program.

Even before the Great Recession a National Bureau of Economic Research study found “that fraud detection does not rely on one single mechanism, but on a wide range of, often improbable, actors. Only 6% of the frauds are revealed by the SEC and 14% by the auditors. More important monitors are media (14%), industry regulators (16%), and employees (19%).”

This is exactly why Congress created the SEC’s Whistleblower Program through the Dodd-Frank Act after the Great Recession. Congress understood that the limited resources of a government regulator were never going to be adequate to protect against the risks these schemes posed to our economy. Empowering whistleblowers to provide tips on where and how fraudulent transactions were happening was the most effective way to prevent fraud.

Tomorrow we will discuss how whistleblowers have already proven their worth in the SEC’s relatively new program.